Sid Hamilton

March 2, 1951–January 21, 2016

This isn’t going to be a regular bio.

A recitation of places and dates, jobs and life events, doesn’t begin to communicate who Sid was, who I knew him to be. So there will be embellishment and digressions, Sid’s life seen through the filter of my experience of living with him for most of our lives. I can’t do his story justice. We are all unknowable in the deep, private, mysterious realms of our inmost lives. I’ve found that the best way to look into Sid’s life is to look at, really look at, his photographs. But here’s a bit of story to go with the pictures.

Sid Hamilton was born in Clayton, New Mexico in 1951.

He grew up on a ranch called Travasilla. It was named after an ephemeral creek that runs through the sere, violently beautiful northern reaches of Union County. His grandfather, Andy Hamilton, reputed to be the meanest sheriff in Union County history, homesteaded the place in the early 1900s. Sid’s father, Hal, was born there in a sod dugout. By the time Sid came along there were real houses, windmills, lots of cows, and miles and miles of creek bed and red rock to ramble. I believe his early experience of immersion in that landscape, that limitless sky, the untrammeled freedom of all that space, shaped his unique vision of the world, and perhaps triggered the great hunger he had to capture evanescent moments—often flashes of beauty only he could see—and marry them to the solidity of a physical object—a photograph. When he was in eighth grade, Sid’s sister’s husband gave him a camera and from then on he had in his hands the instrument that both shaped and served his artistic drive and vision.

He spent his school years in Clayton. In high school he played basketball and kicked field goals well enough to earn the nickname “Golden Toes,” and a scholarship to UNM. He worked at the local newspaper setting type by hand (yes, they really did that in living memory!) and honing his photographic skills.

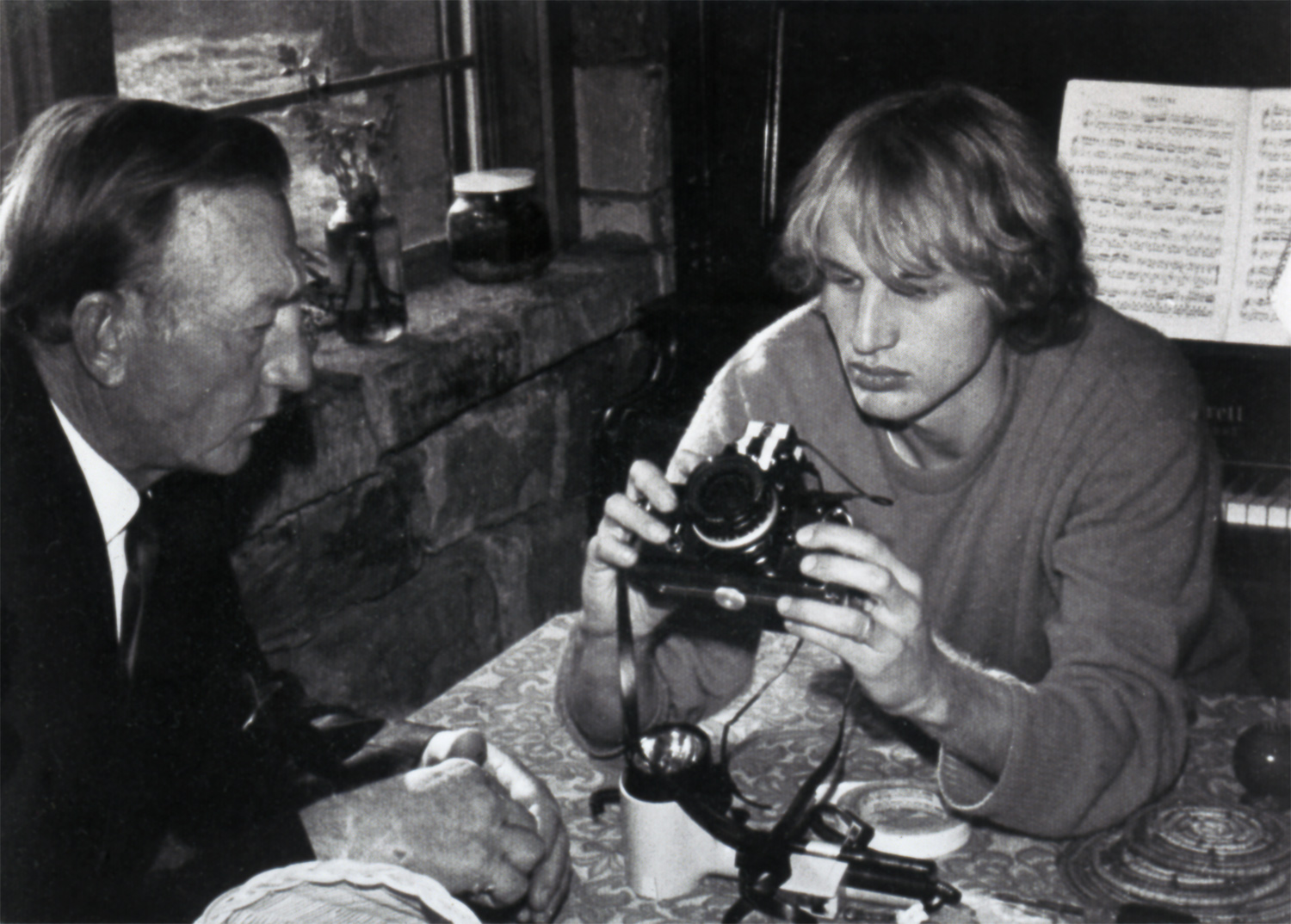

There were a couple of years in and out of college at NMSU in Las Cruces, a year or so of rambling about and then Sid bought the Hasselblad and the darkroom equipment and set up shop. Soon after, Sid’s story became our story and I can’t really untangle the threads that were so closely entwined for 42 years.

We met on a bright, windy morning in June, 1974.

He was standing on his porch and his white t-shirt was so dazzling in the sun I remember I had to shade my eyes. He had a small black cat on his head (Diablo, the mad kitten). His hair was long and blonde and his eyes were a shade of blue I’d never seen and still can’t find a word for. Teal. Deep aqua. Ultramarine. All those. I swear he looked like a Greek god to me, Adonis, most likely, though I didn’t know my Greek gods then and I also didn’t know the Greeks’ wonderful explanation of what happened to us as we stood there in a moment so strange and still and breathless it escaped the constraints of time and remains as strange and breathless as it was forty-some years ago. Pierced by the arrows of Eros. I’m not kidding. A few weeks later—12 to be exact—we were married in a dry riverbed near Gallinas Canyon outside of Las Vegas, New Mexico. To tease our son I’ve always said we were married in a tree, and it was almost true. I did hop up on the lowest branch of a juniper tree to recite my vows. We were feted by crows and lizards and a few good friends.

On our honeymoon trip across the Southwest we visited the Grand Canyon. Sid pretended to fall in. He disappeared over a cliff, yelling. I thought my heart would stop. I ran to the edge of the precipice and found him standing on a ledge just out of sight. This was my first taste of Sid’s peculiar sense of humor.

We settled into an old adobe house in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Sid built a beautiful darkroom in a small adobe casita behind the house. We lived there for a few years and then moved to Santa Fe. Wherever we lived, Sid always had a darkroom and studio. Our lives centered on photography as vocation and avocation, despite the persistent difficulties of trying to earn a living by making art. Sid did all the usual commercial photography stints: weddings, graduations, newspaper photos, portraits, custom printing. He never stopped doing his own work or pursuing his vision. The thousands of images in the archives we are now scanning and curating are a testament to the strength of his drive to make art, no matter what.

In 1980 we moved from Santa Fe to Norman, Oklahoma, where Sid took a job as photography services manager in the marketing department of a large oil field and highway equipment manufacturer. He brought his unique vision to industrial photography there for nearly 12 years, and the demands of that work grew and refined his skills. He traveled all over the country photographing highway construction equipment, and learned more about concrete than I can tell in a few paragraphs. That’s when the prize-winning cover photos of oil pumping units and monster machines made their way into his portfolio. Many of these photos recall to me the icons of early 20th century industrial photography.

In 1982, Sid went to Greece with photographic intent. The results speak for themselves. He had a photojournalist’s instincts and a way with people. I love the way he captured people, moments. But I especially love the landscapes, the subtlest ones, in which the variegations of green manifest in black and white as compositional elements. Which makes me think of all the times Sid and I talked about composition, framing, aesthetics—the nuts and bolts of making, and the challenge and deep pleasure of making. It was a decades-long conversation.

1983. Our son, Alan, was born. Sid so loved being a dad. And Alan was, hands down, the most photographed kid on the block. During those years in Norman we had lots of family close by—Sid’s sister, Julaine, her two young boys and husband, Ron; two of my sisters and their kids. It was one of the happiest times for us.

Then the economy tanked and Sid was laid off from his job. He did a stint teaching at a local college, and in the evenings he plunged into learning programming the way he learned everything else—by simply doing it. In a couple of years he was adept enough to work as a consultant on a variety of IT projects. In 1992 we moved back to New Mexico and Sid started working with brother-in-law Mark Conkling in his real estate development company, and doing contract programming on the side. Through it all, he was never without a camera slung over his shoulder or tucked behind the seat of his pickup.

In 1998 he answered a call to upgrade the computers in an Albuquerque company called Construction Reporter.

It turned out to be much more than that; to be, in fact, the beginning of a truly remarkable story of Sid creating on another level, in another medium. He sort of accidentally became an entrepreneur. He became the nerve center of the business, its IT infrastructure and its visionary developer all in one. We bought the company in 2008 from the son of its founder, and embarked on the oddest, most astonishing, most humbling and elevating adventure of our lives. The challenges that accompanied suddenly owning a business—all the daily decisions, mistakes, triumphs, crises—required that we work closely together, laboring up a steep learning curve. This was, for me, and I believe for Sid, the most deeply rewarding time in our journey together.

I should chronicle Sid’s accomplishments in creating a company culture that we were both proud of. He had an unswerving commitment to our customers and employees, to deliver tools and processes that made their working lives better. He loved our employees like family and insisted that they come first whenever we had to make hard decisions about allocation of resources. He loved his work—the daily labor of creating a product, a piece of software, a customer interface that was robust, unique, well-designed, and most of all, useful. This labor captivated his energy and attention for more than 15 years.

In July, 2015, less than a month after the death of one of two beloved nephews who died that summer and to whom this site is also dedicated, Sid was diagnosed with leukemia. For six months he struggled with the pain of intractable shingles and the effects of chemotherapy. But he kept on making beauty, as he always had. He spent all the time he could in those months taking photographs, selecting, editing, printing them, putting them up on the walls, scrutinizing them as if they held deep truths, untold secrets. They do.

—Rochelle Williams